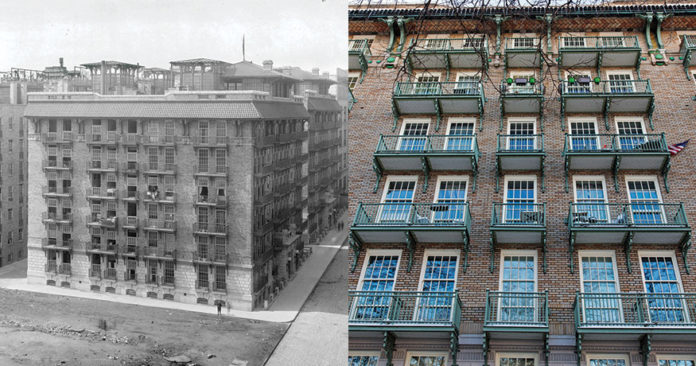

The architect for these model tenements, Henry Atterbury Smith, rethought the whole window idea, not only getting light and air inside the apartments, but also getting the tenants outside.

At the turn of the last century, reformers became more and more interested in improving the housing of low-income wage earners. Dark hallways and stairwells were a particular target; in 1910 American Architect, describing the traditional tenement, said, “No part is more subject to horrors, physical and moral, than halls and stairs.”

Smith developed an unusual plan for an apartment building. He had the idea of leaving each stair tower open to the air, and giving each apartment an outside door opening onto the stairway. He saw this as replicating, in a small way, the householder’s desire for a single house, separate from its neighbors. More important, he viewed the open stairs as a great advance in healthfulness, discouraging the spread of tuberculosis.

He and others persuaded the philanthropist Anne Harriman Vanderbilt to finance a project, and she bought a site at the foot of East 77th and East 78th Streets, at the East River. In 1909 work began on what remains the most ambitious model tenement in New York.

Now called the Cherokee Apartments, the six buildings were also known as the Vanderbilt model tenements, the East River Homes and the Shively Sanitary Tenements, after Dr. Henry Shively, a tuberculosis specialist. As carried out, Smith’s design is unlike anything ever seen, before or since, in low-income housing in New York.

Inside, the two- to five-room apartments were modest. But they show an art borne of intelligence and imagination. Sanitation was a ruling concern. The floors are concrete, to prevent tacking down carpets or linoleum–any carpeting had to be removable, so it could be cleaned. The concrete curved up onto the wall, so as not to trap germs and dust. Radiators were mounted on the walls, so a broom could pass easily underneath.

Smith’s hallways and stairs were another innovation. Although open corridors had appeared before, he reworked the system to a fine degree, with stairways wrapped around a wide central shaft.

The stair-hall walls are covered in glazed brick, the ceilings in Guastavino tile, and they were protected at the top by astonishing, story-high glazed skylights, with side ventilation to generate moving air in the stair halls. The skylights, now gone, looked as though a Bauhaus engineer had squared up one of Victor Horta’s Art Nouveau subway kiosks in Paris.

Now to the windows: Remarkably, most are floor-to-ceiling and triple-hung, which means there are three sashes, not two, allowing a much wider opening than in the usual case. When they are fully raised, it is easy to step through them onto the building’s wide iron balconies. Far from being fire escapes, these balconies were designed for people with mild tuberculosis: They are for taking in fresh air and even sleeping.

To protect the balconies, Smith called for a sloping roof to project beyond the building. Called a pent eave roof, it was covered in red tile, supported by iron brackets that resembled the detailing on the 59th Street Bridge. And Smith made extensive use of glazed polychrome terra cotta. The Vanderbilt tenements have more interest and diversion than a dozen top-end apartment houses.

That was apparently a problem, because in 1913 Smith wrote in The New York Times that all model tenements, even his, had been a failure: They had wound up being too expensive for the low-wage earners they sought.

Listings from the 1915 New York State census confirm this, with tenant occupations like chemist, salesman, actor, secretary and opera singer. There were just a few “dirty hands” occupations, like “paper box scorer” and “cigar packer,” this being the Cuban-born Jacob Alvarez, 45, who somehow packed his family of nine into one of the apartments.

The building, a designated New York landmark, is now a co-op, and propertyshark.com indicates that most recent apartment sales have been in the $250,000-to-$450,000 range, just a few breaking half a million.

Allen, of CTA Architects, is just finishing up a complete replacement of all the wooden windows in the buildings. These bear no resemblance to the usual “replacement window” seen in New York apartments. They are solid mahogany, shoppainted in Ireland, and they slide up and down like a breeze. Stepping out onto a balcony is like going through a porch door.

Allen, a partner in the firm, says the coop board will not allow discussion of the project’s cost. But there are 878 of the larger, triple-hung windows, and 362 regular double-hung windows. Contractors familiar with wooden window replacement estimate the cost per window as $3,000 to $6,000. With 1,240 windows, that’s around $5 million. But then, they are indeed magnificent–truly model windows.

Author: Christopher Gray, NY Times