“He got rid of the intellectual elites,” said my guide. “Brutal—but I think it saved our country. I mean, consider what happens to a place when workers are devalued…”

I was dazed by his words. It was a bizarre mixture of tribal truth and extremism—a far cry from the Southeast Asians that, as a kid, I was told we were fighting to save from the certain death of communism.

The day’s hike in the Cambodian forest was merciless in the 100-degree heat. His words sucked what little breath I had left from my lungs. My mind circled the broken English as I wrestled with his view in my thoughts. He: from ground zero of the Vietnam war and its aftermath. Me: A television witness and collector of voices from my childhood.

“You’re talking about Pol Pot and the killing fields?” I inhaled a deep, humid breath.

“Yes,” he replied without breaking stride.

“You’re talking about the guy who wiped out a fifth of your population?” I quizzed still not believing what I heard.

“Yes,” he said without hesitation.

I increased my pace as I pushed through the thick forest of memory and history. His words abruptly triggered the facts, the politics, the pain. All of which unwittingly divided my country into those who went to college and those who went to war.

My holiday hike that day was memorable in many ways. Allow me to crystallize two—the seeds of untruth planted long ago continue to grow even today. And the American labor problem is generations in the making.

For the record, Cambodia continues to suffer from the terror inflicted by Pol Pot savaging his country’s population, beginning with the college educated. And the U.S. still suffers from the unintended legacy of dividing young men into students and warriors, and then assigning social and moral value to their lot.

Tinker with a nation’s workforce and you’ve changed its future. Even more alarming is that the attack on our founding principles came from within.

Our nation’s Calvinist work ethic has a fundamental tie to opportunity and the soul of our citizenry. Hard work is a moral principle and every contribution, especially the “dirty jobs” is equally necessary to its strength and potential.

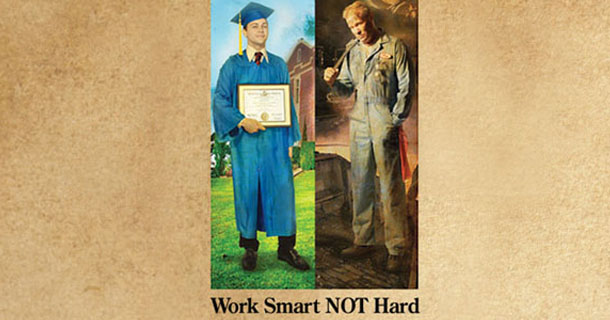

One of the smartest and hardest working guys out there—television personality, Mike Rowe, uses the 1970s ad campaign, “Work smart, not hard,” as a symbol of the moral re-assignment of hard work that began after the Vietnam war. Those fortunate enough to return from Southeast Asia were suddenly displaced in a society that had moved on to a new world and new technology, and they found themselves marginalized a most significant way—the ability to earn a living.

In decoupling hard work from success, Rowe believes we’ve tipped the scales of our workforce and created a skills gap that pushes young people to a four-year degree that could mire them in debt for a lifetime.

How the country derailed from its core belief in opportunity and hard work in the vocational trades to such an imbalance yields a dismal outlook, the likes of which we are only just beginning to feel.

Many of us hail from blue collar roots, especially in the multifamily housing business. Construction tradesmen have laid the foundation for America’s greatness: those who build our homes from the ground up, those who manage them and those who maintain them.

America has much to show for the fruits of our laborers. We must not only honor and value this contribution, but acknowledge that it is vital to our very existence.

Class warfare is so unbecoming a nation built on ingenuity and hard work.

Hard work built the American Dream. And hard work will bring it back.