Not counting the District of Columbia with a population density of 11,535 people per square mile (p/mi2) while the smallest area in the country, the densest state by population is New Jersey with a population density of 1,228 p/mi2. Rhode Island is close behind with a population density of 1,026 p/mi2. What makes these two states unusual is the fact that they are also amongst the smallest states in the country.

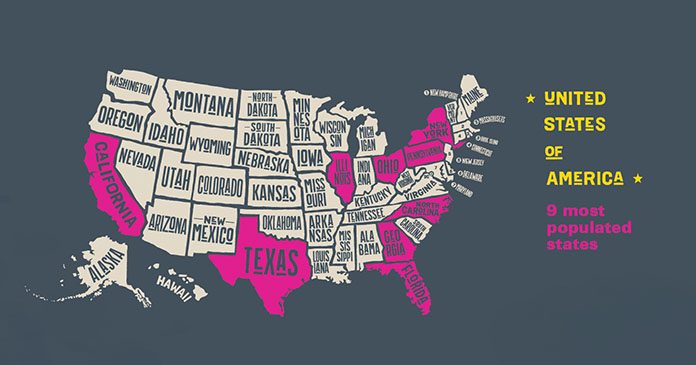

California, the most populous state, has a population density of 255 p/mi2. The next most populous states are Florida (397 p/mi2) and New York (421 p/mi2).

Which brings us to the brilliance of the U.S. Electoral College. The nation’s founding fathers realized even hundreds of years ago that uneven population distribution could result in highly populated states that could easily dominate national elections.

The electoral college is established by the Constitution as a compromise between a vote in Congress and the popular vote by qualified citizens.

Just a refresher: The Electoral College consists of 538 electors. A majority of 270 electoral votes is required to elect the President. Each state’s entitled allotment of electors equals the number of members in its Congressional delegation: one for each member in the House of Representatives plus two for its Senators.

Under the 23rd Amendment to the Constitution, the District of Columbia is allocated 3 electors and treated like a state for purposes of the Electoral College.

Each candidate running for president has his or her own electors by state. The electors are generally chosen by the candidate’s political party, but state laws vary. American citizens, when voting for president, are actually voting for their candidate’s electors.

Most states have a winner takes all system that awards all electors to the winning candidate in their state. Maine and Nebraska are exceptions with variations of proportional representation.

The benefit to the electoral college is that urban metros with large populations do not dictate the outcomes in national votes.

Coalition to change Electoral College

Five times in U.S. history, the presidential candidate who won the national popular vote did not win the White House—including two of the last five elections. Those losses have spurred a national movement to change the way elections are won.

Since Democrat Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 race, with nearly 3 million more votes than Donald Trump, a number of states have passed laws to award their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote. Fifteen states and Washington, D.C., have so far enacted such laws—with the latest, Oregon, joining in June.

It’s a movement that’s been growing since 2006, when the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact—a non-profit with the goal of enacting a system to elect the popular vote winner—formed to persuade states to join.

“The purpose of this legislation is to guarantee the presidency to the candidate who gets the most votes in all 50 states and the District of Columbia,’ National Popular Vote Director John Koza said.

The compact began five years after George W. Bush took office after winning the 2000 election, despite losing the popular vote to Al Gore by about 500,000 ballots. The same thing happened to deny Grover Cleveland in 1888, Samuel J. Tilden in 1876 and Andrew Jackson in 1824.

How it would work

Presently, a state’s electoral votes go to the candidate who wins the state popular vote. But there is no law that requires states to award their votes this way. Each state can decide how to award their votes, which is why some are now split by districts.

If enough states join the movement— those that carry 270 votes or more—the compact would take effect. Until it reaches the 270-vote mark, however, all states will continue to award votes the traditional way.

Proponents argue that the National Popular Vote would give every American voter an equal say in the election. Right now, the argument goes, many Democrats in heavily GOP states and Republicans in solidly progressive states see theirs as wasted, or meaningless, votes.

Also, Koza added, the current system encourages candidates to focus their campaigns on just a handful of key states, called “swing” or “battleground” states. It’s why Republican candidates almost never stump in Hawaii and Democrats nearly always bypass Utah, for example.

“I’m excited about the National Popular Vote coalition because I think it will encourage candidates to spend more time in states like ours,” Oregon Gov. Kate Brown said when she signed the new law. “I think it’s really important for Oregon to be part of the national conversation regarding the presidential election.”

In the 2016 election, 94 percent of campaign events took place in 12 states where Trump’s support was between 43 and 51 percent, while two-thirds of all events were in Ohio, Florida, Virginia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Michigan, according to the coalition.

If and when it reaches the 270-vote mark, the interstate compact would take effect on July 20, meaning it could influence the 2020 presidential election if the remaining needed states join in time.

Where do the states stand?

The 15 joined states and Washington, D.C., bring a combined total of 196 electoral votes—meaning the movement needs to sign up states with 74 more to give the compact legal force.

States that have joined are California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont and Washington. Washington, D.C., has also joined.

Will the remaining 74 electoral votes come? Right now, legislation to join has passed at least one legislative chamber in eight states—Arkansas, Arizona, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Nevada. Those states, if they enacted their bills, would put the compact over the top, with 271 electoral votes.

The Maine Senate in May passed legislation to join, but it was defeated in the House. The same happened in Nevada, where the legislature passed the bill, but it was vetoed by Gov. Steve Sisolak. The governor argued the movement could give smaller states like Nevada less influence in elections.

“It could diminish the role of smaller states like Nevada in national elections and force Nevada’s electors to side with whoever wins the national popular vote, rather than the candidate Nevadans choose,” Sisolak said in a statement after his veto.

Legislation to join the movement has been introduced in all 50 states, but 10— including Florida, South Carolina, Virginia, Texas, Indiana, Iowa, Wyoming and Idaho—have declined to give it a hearing. Florida is considered a key battleground state in each presidential election.

If the movement succeeds, it would seem to align—and clash—with the will of most Americans. A Gallup poll last month found 55 percent of respondents favored eliminating the Electoral College, while 43 percent opposed. However, most (53 percent) rejected the idea of states circumventing the college in the fashion the national compact is attempting.

Source: Demographics, PRO staff, Coalition to change Electoral College section, Daniel Uria, UPI